* See 10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: thoughts and 10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: Columbia students rally to support US troops Spring 2003.

It's been 10 days. I've posted my thoughts on the 10th anniversary of OIF here, and shared my views on OIF in comments at Blackfive, Small Wars Journal, National Review, and Foreign Policy. That's enough.

Here's a good recap of the Duelfer Report. It confirms that we dodged a bomb by ousting Saddam, but OIF critics care more about the bullets that hit us while we dodged the bomb.

Views on Operation Iraqi Freedom haven't changed. They've just hardened. OIF supporters list the many justifications and the bad alternatives. OIF critics coalesce mainly around three points: the conviction that Bush lied, the cost, and the insistence that OIF made matters worse. The 'Bush lied' crowd ignore the justifications and the alternatives. They will stubbornly restate the one point and use it as a platform to legitimize every conspiracy. The 'cost' crowd either decries the whole mission or they support the war while decrying the post-war. The 'made matters worse' crowd is the 'I told you so' folks who are most likely to be nostalgic for Saddam.

My approach to discussing OIF has mainly focused on the contemporary context of wearing Bush's shoes at the decision point. I prefer to ask 'Why Iraq?', rather than the hindsight question of 'Was it worth it?'. I believe answering the 2nd question requires knowing the answer to the 1st question, and most people don't really know the answer to the 1st question. I have found that a better understanding of the context of the decision point at the start of OIF makes a difference in people's views.

For my final thoughts on the 10th anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom, here is a selection of comments I made at the aforementioned sites:

In these comments, it's apparent that a lot of folks fundamentally misunderstood the procedure that led to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clarifications:

Saddam's guilt was established in fact. Legally, Iraq's presumed guilt was the foundation of the Gulf War ceasefire and subsequent UNSC resolutions.

Based on the presumption of guilt, the burden of proof was entirely on Saddam to prove Iraq was rehabilitated according to weapons and humanitarian standards of compliance.

There was no burden on the US or UN, or the various intelligence agencies, to find or prove Iraqi violations.

UNMOVIC, like UNSCOM, was not designed to find Iraq's violations. UNMOVIC, like UNSCOM, was designed to test Iraq's compliance.

While weapons and humanitarian issues were the object of the compliance standards, the main subject purpose of the compliance standards was to test Saddam's behavior and intentions, and thereby resolve Saddam as a regional threat. (Note: Iran is not Iraq's only neighbor in the region.)

This criminal metaphor should help folks understand the rationale behind the enforcement of the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions that led to OIF:

Saddam was like a convicted yet unrepented dangerous recidivist (insert your felonies of choice) who lived in a residential family neighborhood. The label psychopathic could fairly be applied to Saddam. Folks don't much like his troublemaking direct neighbor, either, and were worried - but not too worried - when, at first, they were only making trouble for each other. But the trouble escalated between them and Saddam crossed taboo lines in their fight. That was bad. But Saddam made it worse when he then attacked, hurt, and threatened his other neighbors. Authorities intervened and Saddam was placed on a strict probation status with conditions he must meet in order to prove his rehabilitation. Probation status means you're no longer presumed innocent until proven guilty. Saddam was proven guilty and he held the burden to prove he was rehabilitated. Saddam could and should have met his burden and thereby removed the probation status in year one. Instead, Saddam thought he could beat the system. He perhaps failed to appreciate the high risk that was assigned to him or, perhaps, he did appreciate it and just reverted to his nature as a dangerous recidivist. Saddam continued to violate his probation and the probation became stricter in response. Finally, the authorities declared Saddam's Iraq had "abused its final chance" (President Clinton, Dec 1998). Saddam was given a 2nd final chance to rehabilitate by President Bush in 2002-2003, but Saddam failed again. And the 2nd final chance really was Saddam's final chance.

A main purpose of the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions was to ensure that Iraq would not threaten the region again. Saddam's failure at the compliance tests showed that he was not rehabilitated and remained a threat. Keep in mind that concurrent with the weapons standards, Saddam was noncompliant on humanitarian standards, too.

Bottom-line: While WMD was a chief form of Iraq's threat, the essential threat of Iraq was not possession of WMD. The essential threat of Iraq was the noncompliant, non-rehabilitated Saddam.

The end state for Iraq established by President Clinton and carried forward by President Bush was an Iraq in compliance, internally liberally reformed, and at peace with its neighbors, with or without Saddam. All three prongs have been achieved, though the 2nd prong is less to our standard than the other 2 prongs.

Under the 1st President Bush, the premise that Saddam would remain in power was based on the assumption that Saddam would rapidly comply with the ceasefire terms - in other words, meet his terms of probation. The 1st President Bush did not intend to contain Iraq indefinitely.

Except Saddam didn't comply. Instead, he made the situation worse and increased the standard of compliance.

When the disarmament failed and turned into de facto containment, Clinton threw out the accompanying premise that Saddam would remain in power. Instead, Clinton set the policy that Saddam would remain in power only if Saddam complied and instituted radical reforms to his regime.

By the close of the Clinton administration, we only had 3 choices with Iraq: Maintain indefinitely the toxic status quo ("containment"), free a noncompliant Saddam, or give Saddam a final chance to comply.

The containment was de facto; it was neither our policy with Iraq nor an end state. After Clinton exhausted all enforcement measures short of ground invasion, the containment was what we were forced to do in the absence of a viable alternative.

Freeing a noncompliant Saddam was out of the question.

Op Desert Fox set the bar at a "final chance" for Saddam to comply. The case and precedent for OIF were already in place. Giving Saddam a 2nd and final 'final chance' to comply only needed sufficient political will.

The status quo was toxic, costly, and unstable before 9/11. One way or another, with or without 9/11, we were going to crash land with Saddam. We could either try to control the landing by resolving the Iraq problem on our terms or maintain the status quo while waiting for Saddam to determine our fate. 9/11, by adding the risk of an unconventional front that Saddam could use by his own means or supplying the NBC black market, provided the political will for giving Saddam a final chance to comply.

President Bush moved to resolve the intractable Iraq problem that he inherited. The alternative choices weren't better.

Bush didn't actually take us to war with Iraq. He took us to the compliance test for Saddam with a credible threat of ground invasion. Saddam could have precluded OIF by complying with the weapons, humanitarian, and other standards, and thereby meeting the terms of Clinton's end state for Iraq.

End state ≠ exit strategy.

We achieved our war objectives in Iraq. While the controversy of OIF is fueled mostly by the costlier post-war, our desired end state in Iraq required that we stay to win the post-war in Iraq, too.

One of President Bush's main objectives for giving Saddam a final chance to comply in 2002-2003 was to bolster the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation. Bush faithfully followed the enforcement procedure on Iraq he inherited from President Clinton, although Bush deviated from Clinton's public case. However, although the UN sanctioned the post-war peace operations in Iraq, UN officials disclaimed the invasion of Iraq. By doing so, UN officials discredited the enforcement procedure that defined OIF, thus weakening the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation.

"Rogue" nations, such as Iran and north Korea, thus have been encouraged to advance their WMD pursuits.

How much study has been given to the idea that most or even all the trouble and outsized costs we experienced in our post-war occupation in Iraq were merely compounding downstream effects originating from the one point of failure to establish security and stability after Saddam?

And, if the *one* variable, SASO, had been flipped - if we had been able to establish and guarantee security from the outset of the immediate post-war - everything else about our peace operations in Iraq would have been different?

By curing which early 'viral vectors' could we have headed off the whole epidemic?

My understanding of the Iraq insurgency is that it was rooted on the Sunni side by Saddam loyalists, renowned for their own viciousness, welcoming in al Qaeda. And on the Shia side, the insurgency was rooted in Iran-sponsored Sadrists.

The Kurds were on board with us.

I can't think off the top of my head what could have been done to prevent the Saddam loyalists from mobilizing, but in hindsight, the Shia insurgency strikes me as having been preventable.

We didn't account for Muqtada al-Sadr because he was a minor figure in the Shia community before the war, while the major Shia leaders were on board with us. The coalition believed, with reason, the Shia, like the Kurds, supported our intentions for post-war Iraq. And most Shia did. It seems that if we had been able to identify Muqtada as a threat and neutralize the Sadrist threat early on, we would have stabilized the Shia.

Then that would have left us with only the Sunni problem. The Sunni problem may have been manageable if, like the Sadrists, we have been able to identify and cure the 'viral vectors' early enough.

It's barely remembered now that the international community was prepared to invest and pour peace-building assets into Iraq in the post-war, but only if we guaranteed security in Iraq.

In order to build a higher order social-political society, the universal needs of security and stability first, then law and order, services, and economy - the basics of governance - need to be in place. The insurgency basically beat us to 1st base on security and stability, and the rest of it couldn't work without the foundation. I believe most Iraqis were on board with our promise to build a better Iraq after Saddam. But a minority willing and able to force their politics by extreme violence will have an outsized effect.

The inefficient "adhocracy" in the management of the Iraq reconstruction was in large part due to hostile politics within the US, politically driven unreasonable expectations of immediate returns on investment, and adverse conditions on the ground that sabotaged reconstruction efforts.

If the domestic political frame can be fixed, a reasonable long-term planning approach applied, and initial security and stability mastered, then combined with general improvements, the cost of peace operations should be further driven down.

Of those 'ifs', the most important is establishing and maintaining security and stability from the outset of the post-war.

I believe most or all the inefficiencies in post-war Iraq followed from the initial failure to establish and maintain security and stability. Flip that one switch, and I believe the rest would have fallen into place for us in Iraq, including many fewer casualties for all parties, reasonable expectations and cost management on a long-term planning frame, a conducive political frame, and enough international funding and peace-building assets to reasonably offset our costs.

Regarding the insurgency, 2 nasty surprises:

Saddam loyalists, renowned for their own viciousness, welcoming in al Qaeda.

The Iran-sponsored Sadrists. Muqtada al-Sadr was at best a minor figure in the Iraqi Shia community. We didn't account for him. The major Shia leaders were on board with the US-led coalition. The coalition believed, with reason, the Shia, like the Kurds, were good with our plan - and most Shia were. But not all. The coalition forces were focused on the Sunnis and were surprised by the Jaish al-Mahdi attacks.

From what I've heard, most Iraqis were on-board with the US promise of building a liberal democratic Iraq after Saddam. But in order to build a higher order social-political society, the base of security and stability first, then services (governance) and economy need to be in place. The insurgency basically beat us to 1st base on security and stability. The insurgency did not represent the majority of Iraqis and, indeed, caused massive death and destruction to the Iraqis, but a minority willing and able to be very very violent can have an outsized effect. In politics, violence works.

Here's another angle to consider the justification for Bush's decisions on Iraq:

What debt of honor did we owe Iraq's Shiites for encouraging rebellion in 1991, including a pledge of support from the American President, only then to turn our backs when they took as at our word and rose up against Saddam? The penalty for the crime of trusting America was Saddam brutally putting down the revolt and subsequent reprisals while we assuaged our guilt by adding UNSC resolutions and the no-fly zone.

President Bush’s decisions on Iraq, especially his call on the Counterinsurgency “Surge” in 2006 despite tremendous pressure to cut and run from Iraq, stand in sharp contrast to his father's decision in 1991 that dishonored America in the precise moment that the world’s faith in America as a transformative “leader of the free world” was at its highest. Which signaled to Saddam at the outset the limit of American will to enforce the ceasefire, which set the path for our compounding problems with Iraq.

What we did to Iraq's Shiites in 1991 is why I can’t go all in on hating on Muqtada al Sadr. He’s a villain who’s caused a lot of damage no doubt, but he’s also a villain with a sympathetic origin story. Teenage Muqtada’s father and uncles were killed for trusting America and answering our call to action. While I view him as a problem that needed solving, I didn’t fault Muqtada for distrusting Bush’s son (through no fault of W's) and being murderously bitter against America. I wouldn’t forgive us either if I was in his place.

I can only imagine the level of trust and faith that Iraq's Shia had in America in 1991 to risk their lives and rise up against Saddam on the mere word of the American President. I can only imagine their grief and fury at America's craven self-serving betrayal. If we had kept our word to them in 1991, I wouldn’t be surprised if Muqtada became a cheerleader of the US, instead of an obsessed hater of the US.

It’s too bad because in 2003, when we entered Iraq, the major Iraqi Shia leaders were on board with the American goals for Iraq after Saddam. We failed to account for Muqtada because he was a minor figure. One wonders whether our nation-building occupation of Iraq would have unfolded differently if the Shia, like the Kurds, had stayed on board so that we could have focused on working the Sunni problem.

As is, the Sadrists and JAM surprised us, mixed lethally with the Saddam loyalists and their AQI guests, and it got a lot worse before the COIN “Surge” and Awakening. The interest accrued for Bush the father's debt of honor cost us and the Iraqis greatly.

Our hope, which admittedly was optimistic, was that Iraq's sectarian mix would become a model for liberal pluralism in the Middle East. The US position was that Iraqis would come together as Iraqis first.

From President Clinton's statement on signing the Iraq Liberation Act, October 1998:

The United States favors an Iraq that offers its people freedom at home. I categorically reject arguments that this is unattainable due to Iraq's history or its ethnic or sectarian makeup. Iraqis deserve and desire freedom like everyone else.

I'm late to the party, but here are my thoughts on Saddam in relation to Iran:

Saddam nostalgics are delusional.

Iraq and Iran are not the only 2 nations on an island. Saddam threatened the whole region and especially his other closest neighbors. Has everyone forgotten that we fought the Gulf War because of attacks and threats against his neighbors other than Iran?

The Iran-Iraq War was not a stabilizing event. Saddam-Iran is not a case of adding 2 unstable elements to form a stable compound. This notion of propping up Saddam to deal with Iran for us is like proposing the propping up of Hitler to deal with the Soviet Union for us. Hitler + USSR = worst of WW2, not peace in our time. Propping up Saddam to deal with Iran is not a recipe for regional security and stability.

Enough people already claim America's liberal promise as 'leader of the free world' is a lie. If we decided to reverse course and prop up Saddam after a decade enforcing UNSC and Congressional humanitarian resolutions and statutes for Iraq, all those people would be right.

Saddam was not our puppet to control. If we decided that a *noncompliant* Saddam should remain in power, how do we expect to control Saddam's behavior inside Iraq, in the region, even on the international level, given his track record and ambitions? Remove our constraints from the noncompliant Saddam and put on blinders? Make a deal with Saddam with 'rules' we actually expect him to honor?

Most likely, this fantasy relationship with Saddam would require a continuation of our indefinite, toxic, expensive, provocative, harmful, crumbling pre-OIF status quo mission with Iraq. And it probably would not work. By the way, pre-OIF status quo mission nostalgics are delusional, too.

It's like the Saddam nostalgics have wiped their memories of why we fought the Gulf War and tried to enforce the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions in the first place. The Saddam they've conjured up since his death is not the same Saddam we struggled with.

As I said up front, my approach to understanding OIF is based mainly on the contemporary "Bush's shoes" context of the question, 'Why Iraq', rather than the hindsight question of 'Was it worth it'. I believe answering the 2nd question requires knowing the answer to the 1st question, and most people don't really know the answer to the 1st question.

As such, my discussion points emphasize the "political rhetoric" of conditions, laws, policies, and precedents at the decision point rather than a post-mortem technocratic accounting.

"Who knows?"

We knew the standing US relationship with Iraq was toxic, indefinite, deteriorating, and stalemated.

We knew the official US determination - established under Clinton - that the noncompliant Saddam was a "clear and present danger to the stability of the Persian Gulf and the safety of people everywhere."

We knew the direct and second-order harms caused by the US status quo with Iraq.

We knew the laws and policies - established during the Clinton administration - that set the resolution for the Iraq problem.

We knew 9/11 had opened an unconventional front that Saddam could utilize with or without al Qaeda - al Qaeda did not own a monopoly on terrorism.

By the close of the Clinton administration, we knew our only way out of the toxic mess with Iraq, other than regime change (internally or externally generated), was Saddam complying with the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions.

Either/Or.

Both Clinton and Bush gave Saddam a "last chance" to comply. He declined. That left the US with one option for solving the toxic status quo with Iraq.

At the decision point of OIF, did you believe that Saddam would come around on his own accord on both the weapons and humanitarian fronts if we unilaterally ended the pre-OIF mission? Or, the US's Iraq problem would solve itself if we continued maintaining the pre-OIF status quo?

Before and after 9/11, did you believe the pre-OIF status quo with Iraq was stable, stabilizing, and sustainable?

When you place yourself in Bush's shoes at the decision point of OIF, keep in mind the humanitarian standards, too. They were not an after-thought to WMD. In fact, the most costly, invasive, provocative, and (arguably) controversial part of our pre-OIF status quo with Iraq - the no-fly zones with counter-fire - were enforcing humanitarian resolutions, not weapons-related resolutions.

So, even if Saddam had completely and unconditionally met his burden of proof on the weapons-related resolutions, the humanitarian issues still needed to be resolved in order to lift the pre-OIF mission and call off OIF.

There is no evidence, even after the fact, to argue that Saddam was in position to comply with the humanitarian resolutions.

I agree that the faulty intelligence "undermined our credibility globally". Again, however, context matters, and the context has been distorted in the public discussion.

The trigger for OIF was not based on an "assumption" by Bush officials. The trigger for OIF was based on the controlling *presumption* of Iraq's guilt on WMD. Plus, Saddam's violation of the concurrently mandated humanitarian standards is not disputed.

Iraq was on probation after the Gulf War, which meant the CIA was not responsible for proving the state of Iraqi WMD. Iraq's guilt on WMD was established. For the legal purpose of enforcing the ceasefire and UNSC resolutions, Iraq's guilt was presumed. Iraq was responsible to prove it was cured of WMD weapons, related technology and systems, development, and intent. Only Iraq - not the CIA - could cure Iraq's presumption of guilt.

In fact, the CIA Duelfer Report shows Saddam was holding back and Iraq was in violation. We only know (or believe we know) after the fact what Saddam was holding back.

"Assumption" isn't compelling from the legal standpoint on Iraq. As long as Iraq's presumption of guilt was controlling, US officials were *obligated* to interpret intelligence on Iraq in the unfavorable light cast by the presumption of guilt. That was true for Clinton officials as well as their successors.

In any case, we didn't go to war based on the intelligence. The trigger for OIF was Iraq's failure to comply, ie, meet its burden of proof on a mandated standard of compliance.

I explain this further in Regime Change in Iraq From Clinton to Bush, which I wrote for my National Security Law class, and its companion piece A problem of definition in the Iraq controversy: Was the issue Saddam's regime or Iraq's demonstrable WMD?, which explains the divergences in the public controversy.

They're easy reads, but here's the executive summary: Legally, Bush relied on Clinton's laws, policies, and precedents on Iraq, ie, the legal case, to resolve the Iraq problem. Publicly, Bush should have stuck closer to Clinton's public case because Clinton's public case against Iraq hewed close to the legal case against Iraq. That's the difference between a Harvard MBA and a Yale JD, I guess.

As you point out, the decision-point justification for OIF is a separate issue from analysis of the post-war in OIF (ie, occupation and peace operations after Saddam). However, the two issues are often conflated in the public discourse, which is where my decision-point contextual approach to the issue comes in.

On the issue of the post-war in Iraq ...

My understanding of de-Baathification is it did not apply a lifetime bar on soldiers and bureaucrats from government service. Rather re-hiring required a vetting process.

Bremer's plan made sense and the international community was initially willing to pour non-military assets into rebuilding Iraq. But the base requirement for everything else to build on was security and stability, and the enemy blew that up.

What if the military hadn't fallen behind the insurgency? What would be different in Iraq today if the COIN "Surge" has been employed in the 'golden hour' of the immediate post-war, rather than at the end of 2006, and precluded the damage to the peace process wrought by the insurgency?

So yes, I wish our military performance in post-war Iraq had been perfect from the outset, too. But I tend to be sympathetic because I realize the insufficient preparation by the Army for the post-war was caused by a deep-seated institutional flaw - the Vietnam War-traumatized, Powell Doctrine mindset. Our problem in the immediate post-war wasn't primarily insufficient troop numbers; it was insufficient method. Bush could control the numbers, but no Commander in Chief was going to overcome the Powell Doctrine mindset of the military before the fact.

I talk about my pre-9/11 brush with the Army's post-war doctrinal flaws in this post. Pre-mission planning and training wouldn't have solved the Powell Doctrine problem. The only realistic way the US was going to learn how to occupy Iraq properly was to occupy Iraq first, and then be driven to the correct method by necessity, assuming we didn't cut and run before we learned.

I'm also sympathetic because the standard applied by OIF critics to OIF is ahistorical. Getting it dramatically wrong at the start of a war, absorbing catastrophes, and then learning how to do it right along the way, is a consistent theme in US military history. It just happens that in OIF, our learning curve was steeper in the post-war than it was in the war.

For the Army, the road to right has always been paved with a lot of wrong, and a lot of our blood. The key has always been whether the US would stay the course long enough to turn wrong into right. The post-war in Iraq is far from our worst post-war. The Korean War happened 5 years into the post-war of WW2. Truman sent Task Force Smith into Korea on a suicide mission. Eisenhower used public discontent over the Korean War to break the Democratic stranglehold on the White House. Ike campaigned on the promise he'd get us out of Korea ASAP.

The US got a hell of a lot wrong - catastrophically wrong - in our post-war in Korea, but our military stayed long enough to get it right because Eisenhower, despite his campaign promise, established a long-term military presence in Korea to secure our gains that continues today.

If we had been able to control the security from the outset of the post-war, I think events in Iraq would have turned out very differently, even without the COIN "Surge". Still, our learning curve in Iraq, while costly, is consistent with US military history, and the post-war in Iraq looked like it had turned the corner at the point we left. It may still work out, but I just don't know at this point whether we stayed in Iraq long enough to secure our gains and foster a reliable (domestic) peace in Iraq, like we did with South Korea.

That is how the real world works for convicted unrepented defiant recidivists on probation status. They're held to a higher standard of behavior due to the greater risk they pose to society. Probation status means you're no longer presumed innocent until proven guilty. Saddam was proven guilty and he held the burden to prove he was innocent and rehabilitated. A main purpose of the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions was to ensure that Iraq would not threaten the region again, ie, rehabilitation. Saddam's failure at the compliance tests shows that he was not rehabilitated and remained a threat.

My approach to understanding why we invaded Iraq is based on the contemporary context of Operation Iraqi Freedom. In other words, to understand President Bush's decision to invade Iraq, one must place oneself in Bush's shoes at the decision point to invade Iraq.

I believe OIF was a war of choice. I understand the alternate choices to OIF were not better choices.

President Bush faced, as did President Clinton before him, 3 choices on Iraq:

A. The status quo, or maintain indefinitely and head-lining the invasive, provocative, harmful, and eroding bombing, sanctions, and 'containment' mission;

B. Unilaterally end the status quo mission and release a noncompliant Saddam from constraint, in power and triumphant; or

C. Give Saddam a final chance to comply with the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions under the ultimate threat of regime change, and if Saddam triggered the final enforcement step, move ahead with regime change.

Realistically, President Bush could choose either Option-A, the status quo, or Option-C, give Saddam a final chance. Option-B, or free a noncompliant Saddam, was out of the question.

At the decision point of OIF, what did we know about the status quo, Option-A?

We knew the standing US relationship with Iraq was toxic, indefinite, deteriorating, and stalemated.

We knew the official US determination - established by President Clinton - that noncompliant Saddam was a "clear and present danger to the stability of the Persian Gulf and the safety of people everywhere."

We knew the direct and second-order harms caused by the US status quo with Iraq.

We knew the laws and policies - again, established by President Clinton - that set the resolution for the Iraq problem.

We knew 9/11 had opened an unconventional front against the US that Saddam could utilize with or without al Qaeda - al Qaeda did not own a monopoly on terrorism.

By the close of the Clinton administration, we knew our only way out of the toxic mess with Iraq was either regime change (internally or externally generated) or Saddam complying with the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions.

Either/Or.

Both Clinton and Bush gave Saddam a "last chance" to comply. Saddam failed to comply both times. That left the US with one option for solving the toxic status quo with Iraq.

President Bush chose Option-C. If you would have chosen differently, either Option-A or Option-B, then place yourself in Bush's shoes:

At the decision point of OIF, did you believe that Saddam would come around on his own accord on both the weapons and humanitarian fronts if we unilaterally ended the pre-OIF status quo mission (Option-B)? Or, the US's Iraq problem would solve itself if we continued maintaining the pre-OIF status quo (Option-A)?

Before and after 9/11, did you believe the pre-OIF status quo with Iraq was stable, regionally stabilizing, and sustainable?

When you weigh your choice, keep in mind the humanitarian standards imposed on Iraq. They were not an after-thought to WMD. In fact, the most costly, invasive, provocative, and (arguably) controversial part of our pre-OIF status quo with Iraq - the no-fly zones with counter-fire - was enforcing humanitarian resolutions, not weapons-related resolutions.

That means even if Saddam had completely and unconditionally met his burden of proof on the weapons-related UNSC resolutions, the humanitarian requirements still needed to be resolved in order to lift the pre-OIF status quo mission and prevent OIF.

There is no evidence - even after the fact - that Saddam was in position to comply with the humanitarian resolutions.

Again, you're wearing Bush's shoes at the decision point of OIF: Option-A, Option-B, or Option-C?

I agree that the faulty intelligence "undermined our credibility globally". Again, however, context matters, and the context has been distorted in the public discussion.

The trigger for OIF was not based on an "assumption" by Bush officials. The trigger for OIF was based on the controlling *presumption* of Iraq's guilt on WMD. Plus, Saddam's violation of the concurrently mandated humanitarian standards is not disputed.

Iraq was on probation after the Gulf War, which meant the CIA was not responsible for proving the state of Iraqi WMD. Iraq's guilt on WMD was established. For the legal purpose of enforcing the ceasefire and UNSC resolutions, Iraq's guilt was presumed. Iraq was responsible to prove it was cured of WMD weapons, related technology and systems, development, and intent. Only Iraq - not the CIA - could cure Iraq's presumption of guilt.

In fact, the CIA Duelfer Report shows Saddam was holding back and Iraq was in violation. We only know (or believe we know) after the fact what Saddam was holding back.

"Assumption" isn't compelling from the legal standpoint on Iraq. As long as Iraq's presumption of guilt was controlling, US officials were *obligated* to interpret intelligence on Iraq in the unfavorable light cast by the presumption of guilt. That was true for Clinton officials as well as their successors.

In any case, we didn't go to war based on the intelligence. The trigger for OIF was Iraq's failure to comply, ie, meet its burden of proof on a mandated standard of compliance.

The notion that Operation Iraqi Freedom was triggered by faulty intelligence is a persistent, but false myth.

The intelligence on WMD did not and - by design - could not trigger Operation Iraqi Freedom. The only trigger for OIF was Iraq's failure to comply, ie, meet its burden of proof on a mandated standard of compliance.

Iraq was on probation after the Gulf War, which meant the CIA was not responsible for proving the state of Iraqi WMD. Iraq's guilt on WMD was established. For the legal purpose of enforcing the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions, Iraq's guilt was presumed. Iraq was solely responsible to prove it was cured of WMD weapons, related technology and systems, development, and intent. In addition, Iraq was responsible for meeting a mandated humanitarian standard. Only Iraq - not the CIA - could cure Iraq's presumption of guilt.

As long as Iraq's presumption of guilt was controlling, US officials were *obligated* to interpret intelligence on Iraq in the unfavorable light cast by the presumption of guilt. That was true for Clinton officials as well as their successors.

In fact, the 2004 CIA Duelfer Report shows Saddam was holding back and Iraq was in violation. We only know (or believe we know) after the fact what it was that Saddam was holding back. Of course, Saddam's violation of the concurrently mandated humanitarian standards is not disputed.

The intelligence could not trigger OIF. Only Saddam's failure to comply could trigger OIF. In order to cure Iraq's presumption of guilt and prevent Operation Iraqi Freedom, Saddam only had to meet his burden of proof on the mandated standard of compliance for the Gulf War ceasefire and the weapons and humanitarian resolutions. Saddam could and should have complied in 1991, let alone 2002-2003.

President Clinton gave Saddam a "final chance" to comply in 1998. President Bush gave Saddam a second last chance to comply in 2002-2003. Saddam failed to comply in both his last chances on both the weapons and humanitarian fronts.

And, that's why we invaded Iraq.

Our Iraq mission was trending as a success at the point that Obama and Biden badly bungled the SOFA negotiation. It's as though Eisenhower somehow fumbled away Germany, Japan, and Korea, for whom US-led nation-building also required many years, at their critical turning points.

By the close of the Bush administration, the US presence in geopolitically critical Iraq was settling into a stabilizing role like our long-term presence in Europe and Asia. Obama's failure in Iraq has led to, at the very least, a stronger position for Iran, decrease of US options in the region, and the heightened risk of reversing hard-won progress in Iraq. Like Germany in Europe and Japan in Asia, an empowered liberal Iraq should have been the lynchpin of our Middle East strategy. Now, we can only hope the US did enough for Iraq to resist corrupting influences and stand on its own before our premature exit.

Eric

Friday, 29 March 2013

Sunday, 24 March 2013

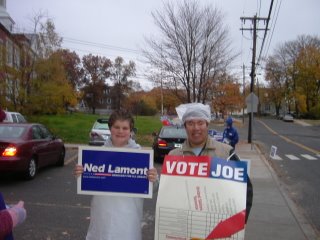

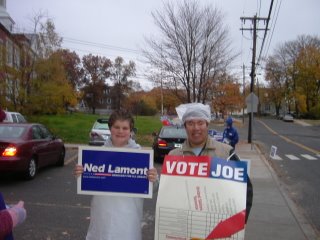

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: Columbia students rally to support US troops Spring 2003

Columbia University students rally on Low steps to demonstrate campus support for American soldiers Spring 2003.

Also see:

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: thoughts;

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: final thoughts.

Eric

Tuesday, 19 March 2013

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: thoughts

On March 19, 2003, President Bush announced the commencement of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Today is the 10th anniversary.

In November 2002, I weighed in on the looming Iraq confrontation in my opinion column for my school paper. My 1st post on this blog was dedicated to Army LT Ben Colgan. I said in my 3rd post that "the central battle of the War on Terror, in the present and for the future, is unequivocally being fought right now in Iraq." In fact, collecting my thoughts on the Iraq mission was the initial catalyst for starting this blog. 171 of my posts carry an "iraq" label ... 172 posts including this one. I've debated the Iraq mission with family, friends, classmates, and professors, on blogs, in on-line forums, and a television special with Iraqi and American college students.

The Democrats' current political advantage over the Republicans, including the presidency of Barack Obama, is built upon the demonization of President Bush over the Iraq mission, despite ample evidence that Bush and the Democrats were on the same page about Saddam. In fact, President Bush inherited the Iraq problem, together with the laws, policies, and precedents to resolve it, from President Clinton. As president, Obama upheld the justifications for military intervention in Iraq, though without endorsing OIF by name.

Given that many influential people are invested in an inimical, knowingly distorted narrative of the Iraq mission, explaining the Iraq mission seems like a quixotic exercise. Nonetheless, I do what I can.

The question that is being asked the most about the Iraq mission is the leading question, Was it worth it? Due to the popular misconceptions about the Iraq mission, however, I believe the most important question on this anniversary still is the contextual, Why Iraq?

Over the next few days, I'll look at my 171 posts with the "iraq" label and accrete my thoughts below. Make sure to check out the links.

Enjoy:

General David Petraeus: “If we are going to fight future wars, they’re going to be very similar to Iraq,” he says, adding that this was why “we have to get it right in Iraq”.

The objectives set forward by President Clinton to resolve our Iraq/Saddam problem were achieved with Operation Iraqi Freedom: Iraq in compliance, Iraq at peace with its neighbors and the international community, and Iraq internally reformed with regime change, albeit progress in the last goal has been less firm compared to the achievement of the first two goals.

To learn about the Counterinsurgency "Surge" in Iraq, I suggest this documentary video, the 2007 year-end letter from GEN Petraeus to his soldiers in Multi-National Forces-Iraq, these e-mails from Baghdad by Army Lieutenant Josh Arthur (a Columbia Class of 2004 graduate who served as an infantry platoon leader in the "Surge"), and the tactical innovations of Army Captain Travis Patriquin (R.I.P.).

President Kennedy explained the Iraq mission to West Point cadets ... in 1962.

Modern political Islamists are totalitarian, a Marxist revolutionary hybrid. Compare their efforts to Mao's Cultural Revolution. Many people seem not to comprehend that the terrorists are engaged in a clash of civilizations with us. In the clash of civilizations, terrorists welcome war. War is the terrorists' vehicle for unraveling the existing order. Terrorists, instead, cannot tolerate our peace. A trend-setting pluralistic liberal Iraq at peace is offensive and an existential threat to the terrorists.

In that light, I offer these essential questions about our commitment, clarity, and Why We Fight:

If American, and Western, progressivism has been conclusively discredited for its forceful displacement of native cultures like the American Indian tribes, then what is the ethical difference, after removing the Lebensraum aspect of autarkic Western expansion, between that and championing a liberal world order today in a 'clash of civilizations' against autocratic Middle Eastern regimes like Syria, Iran, Saddam's Iraq, or the Taliban in Afghanistan, and their fellow travelers like al Qaeda? Are we allowed to be progressive if we cannot, by self-imposed rule, classify our competitors as regressive? What's the practical effect if we restrict our engagement at the same time our competitors are totally committed to establishing an order that is incompatible with, and actively opposed to, our preferred liberal order?

I believe we need to restore our chauvinistic commitment to the American progressivism that shaped much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

I compared the merits of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom at Columbia political science professor Brigitte Nacos's blog in comments here and here. Excerpt:

From President Clinton's statement on the Iraq Liberation Act:

In response to 9/11, the US could have pulled back from the Middle East, supported greater repression in the Middle East, or promoted greater freedom in the Middle East.

President Bush also could have reacted to 9/11 with a narrow focus on hunting down and killing terrorists, like President Obama's drone-centered campaign. (Bush used hunter-killer drone killings, too, but as one tool in the toolbox, not the centerpiece of his counter-terror strategy.) However, President Bush understood punishment and revenge did not amount to a big-picture, long-term solution.

Instead, the centerpiece of President Bush's big-picture, long-term response to 9/11 was revitalizing the American grand promise that animated the "free world" after World War 2. When he officially declared America's entry into the War on Terror on September 20, 2001, President Bush announced a liberal vision on a global scope and warned of a generational endeavor:

President Bush gave us the opportunity to reaffirm that we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our Fortunes, & our sacred Honor in order to battle the regressive challenge to our hegemony and make the world a better place. Instead, Bush's detractors used the opportunity to attack Bush with a false narrative in order to advance their own parochial partisan self-interests at the expense of the Iraq mission, our national interest, and a progressive world order.

Our peace operators - military, non-military, and contracted civilian - have been magnificent. But the rest of us shrank from President Bush's idealistic liberal vision. We the people let down our President, we let down our American heritage, and we let down the world. Rather than rise to the challenge of 9/11 with America's finest hour, we chose the beginning of the end.

Senator Joe Lieberman was an exception. He honored his liberal principles by his resolute support for the definitively liberal Iraq mission and the War on Terror.

Senator Joe Lieberman was an exception. He honored his liberal principles by his resolute support for the definitively liberal Iraq mission and the War on Terror.

The antithesis of Senator Lieberman is President Clinton, the only American who appreciated the Iraq problem equally as well as President Bush. President Clinton initially supported President Bush and endorsed OIF based on Clinton's still-fresh presidential experience struggling with Saddam. However, where Lieberman stayed steadfast despite tremendous political pressure, even at the cost of his party, Clinton eventually caved to party pressure and turned on Bush and OIF.

One of President Bush's objectives for giving Saddam a final chance to comply in 2002-2003 was to bolster the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation. Bush faithfully followed the enforcement procedure on Iraq he inherited from President Clinton, although Bush deviated from Clinton's public case. However, although the UN sanctioned the post-war peace operations in Iraq, UN officials disclaimed the invasion of Iraq. By doing so, UN officials discredited the enforcement procedure that defined OIF, thus weakening the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation.

"Rogue" nations, such as Iran and north Korea, thus have been encouraged to advance their WMD pursuits.

The link between 9/11 and Iraq is not a major part of my take on the issue because the Iraq problem, including Saddam's guilt on terrorism, and procedures to resolve the problem were mature by the close of the Clinton administration, before 9/11. President Bush's implementation of the preemptive doctrine in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks was an extension of President Clinton's preemptive doctrine in response to the escalating Islamic terrorist campaign that culminated in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The Bush administration did not claim Saddam was behind the 9/11 attacks. However, the 9/11 attacks did significantly boost the urgency and political will to resolve the Iraq problem expeditiously. President Clinton explained the link between 9/11 and Iraq:

The accusation that OIF was based on manufactured intelligence or the 'confirmation bias' of Bush officials relies on revisionist premises.

First, Iraq's guilt on WMD was established and presumed as the basis of the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions. The US and UN carried no burden of proof to demonstrate Iraqi WMD. The intelligence did not and could not trigger OIF because the burden of proof was entirely on Iraq. OIF was triggered by Saddam's failure to meet Iraq's burden of proof on a mandated standard of compliance.

Second, based on Iraq's history, track record of deception, defiance, and belligerence, established and presumed guilt, and the stakes involved, Clinton and later Bush officials with the added threat considerations in the wake of 9/11 were obligated to view any intelligence on Iraqi WMD in an unfavorable light for Iraq. As Clinton explained in 2004, "I thought the president had an absolute responsibility to go to the U.N. and say, 'Look, guys, after 9/11, you have got to demand that Saddam Hussein lets us finish the inspection process.' You couldn't responsibly ignore [the possibility that] a tyrant had these stocks".

In fact, because of Iraq's established and presumed guilt and burden of proof, our ignorance of the state of Iraq's WMD - as Clinton framed his cause for war with Iraq - was legally sufficient to trigger military enforcement, though perhaps not politically sufficient. If all of the intelligence on Iraqi WMD was mistaken, then that only returned our enforcement on Iraq to the lower bar of unaccounted for Iraqi weapons that triggered Operation Desert Fox. Solving our ignorance about Iraq's weapons was Saddam's duty. In other words, the intelligence was irrelevant as a cause of war. The failure of Saddam to comply and cure his presumption of guilt was the cause of war both in 1998 and 2003.

President Bush was faithful to President Clinton's Iraq and counter-terrorism policies, and it's unfortunate that Bush deviated from Clinton's public case against Iraq by citing intelligence rather than using the lower bar of Clinton's Iraq-induced ignorance. Nonetheless, Bush's public presentation did not change the US's Iraq problem, the established procedure to resolve the Iraq problem, Iraq's established and presumed guilt on WMD, our 3 choices on the Iraq problem, and the urgency added by 9/11 to resolve the Iraq problem.

The 2004 CIA DCI Special Advisor Report on Iraq's WMD, commonly called the Duelfer Report, confirmed that Iraq was in violation of the UNSC resolutions related to weapons, though not entirely as suggested by the pre-war intelligence. There is, of course, no disagreement that Saddam was in violation of the UNSC resolutions related to humanitarian and terrorism standards.

When the Abu Ghraib scandal exploded, I was ashamed and angry as a former soldier. I knew first-hand the ethical expectations of American soldiers. I felt that the soldiers at Abu Ghraib had betrayed the faith of their fellow soldiers and caused significant harm to the Iraq mission.

However, my anger was mitigated by my appreciation that an extremely violent insurgency had seized the initiative in Iraq and the US-led coalition forces defending Iraq had fallen behind. Their 'how' was offensive and wrong, but their 'why' was understandable. The Abu Ghraib prison guards were not abusive simply for the sake of committing abuse. They were trying to help stop aggressive mass murderers who were committing daily atrocities in Iraq.

As a Senator and presidential candidate, President Obama had over-simplified the "choice between our safety and our ideals" in order to slander President Bush. Like the personnel stationed at Abu Ghraib, Obama quickly learned as Commander in Chief that the responsibility to make life-or-death decisions about a zealous, inveterately murderous, unethical enemy is more difficult.

I posted my first impression of the Abu Ghraib scandal in an on-line forum discussion in June 2004. Excerpt:

From the 16JAN09 Washington Post article, A Farewell Warning On Iraq, by David Ignatius:

The 20MAR13 New York Times article, Seeking Lessons from Iraq. But Which Ones?, by David Sanger shows that their bias against the Iraq mission has handicapped policymakers in the Obama administration. Here's the (truncated) e-mail I sent to David Sanger via the NY Times website:

The question I should have asked David Sanger was, does President Obama's deliberately anti-OIF foreign policy signal that liberalism is dead as the defining and galvanizing principle of American (and American-led Western) foreign policy?

Bush officials have been accused of ignorance about the sectarian fault lines in Iraq. While they can be accused of being optimistic about Iraqis uniting after Saddam - an optimism they inherited from the Clinton administration - it's not true that Bush officials were ignorant about Iraqi differences. Rather, the hope of Presidents Clinton and Bush was that a pluralistic liberal Iraq growing from the ashes of Saddam's regime would serve as a model for the region.

President Obama, too:

Knowing the challenges, however, is not the same as solving them. Bremer had a blueprint for the transition after Saddam. CPA officials understood what was needed in a macro academic sense and their decisions were reasoned, but the CPA was unable to execute Bremer's blueprint in the micro real-world sense. The CPA simply was overtaken by events on the ground and fell behind the insurgents and terrorists, such as the Saddam loyalists, al Qaeda, and Iran-sponsored Sadrists, who used extreme violence against the state, economy, peace operators, and the Iraqi people in order to blow up the nascent peace process.

I believe, based on what I've heard, there was a 'golden hour' in the immediate post-war period. Most Iraqis wanted the better future after Saddam that President Bush pledged to build in Iraq. It's barely remembered now that the international community was prepared to invest and pour assets into Iraq in the post-war, but only if security and stability were guaranteed. As GEN Petraeus warned, "Act quickly, because every Army of liberation has a half-life."

Analogous to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, our higher social, political, and economic aspirations for Iraq after Saddam wholly depended on first establishing the base of security and stability, followed by orderly governance, services, and economy. When the insurgents beat us to 1st base on security and stability, we lost the 'golden hour' and our first, best chance to take control of post-war Iraq. Our higher order aspirations for Iraq couldn't work absent the base of security and stability.

Read my comment on a Washington Post snapshot of early challenges and our hope for Iraq. I also recommend Dale Franks's defense of the CPA decision to demobilize the Iraqi Army.

On the military side, GEN Eric Shinseki famously warned that 500,000 soldiers would be needed to garrison Iraq.

I agree we should have had more troops available at the outset of the post-war, but I don't believe we needed as many troops as GEN Shinseki said we did. In fact, our post-war troop level in Iraq peaked at 157,800 in FY2008. Our main problem in the post-war wasn't the numbers. The main problem was insufficient method (strategy, plans, tactics, techniques, procedures, etc.) for an effective occupation. Despite our history of successful post-war occupations, the regular Army of 2003 simply was not prepared to do a nation-building occupation of the kind needed for Iraq. The Army's post-war shortcomings were mainly due to an institutional mindset rooted in the fall-out of the Vietnam War and exemplified by the Powell Doctrine. The only way the Army would develop a sufficient peace-operations capability for occupying post-war Iraq was to occupy post-war Iraq and learn by necessity.

The standard of perfect preemptive anticipation, preparation, accounting, and execution that critics apply to OIF is ahistorical. Consistent with military history, the learning curve for victory in Iraq was driven by necessity on the ground. Our military has always undergone steep learning curves in war. OIF just demanded a steeper learning curve in the post-war.

That said, it's been reported that a military-led proto-COIN strategy was proposed early on, but was turned down in favor of giving the civilian-led CPA more time. I wonder what difference it would have made if a proto-COIN 'surge' had been attempted in the 'golden hour' of the immediate post-war in Iraq.

On January 30, 2005, a critic of Bush and OIF reconsidered his views after witnessing the Iraqi people risk their lives to vote and passionately participate in Iraq's first free election. The American soldiers who served in Iraq during that time often cite their roles protecting and facilitating the Iraqi election as a highlight of their military careers.

Today, after the partisan vitriol poured onto OIF followed by disappointment with the Arab Spring, it's fashionable to say that the social-political culture of the Middle East is incompatible with liberal reform and President Bush was a fool to try.

I'm not ready to admit that liberal reform in Iraq is a pipedream. I don't equate the violent insurgency by a minority of Iraqis and foreign terrorists to a majority opposition to a pluralistic liberal society by the Iraqi people. As a soldier, I served in South Korea 50 years after the GIs who fought the Korean War. They were disillusioned by the Korean War and had the same doubts that liberal reform would ever take hold with the non-Western Koreans. But it did. From the beginning, experts and government officials cautioned that we must be patient with Iraq because nation-building with liberal reform is a process of fundamental change that requires a long time nurturing - perhaps a lifetime - to bear fruit.

South Korea's first free presidential election was held in 1987. The difference is the US military stayed to protect South Korea after the Korean War. We've left Iraq.

The contest for Iraq pitted the American ideal of consensual liberal civics versus the killing will of the anti-liberal Islamic extremists. As former Barnard history professor Thad Russell repeated the mantra to us in class, in politics, violence works. We can only hope we did enough for the Iraqi people so that they will come together and resist the anti-liberal forces without our help.

Liberal reformers versus Islamic extremists was not the only contest in Iraq during OIF. There was also the contest of ordinary Muslims versus Islamic extremists. After 9/11, I recognized the terrorists had to be alienated from the Muslim mainstream. In the second, perhaps more consequential, contest in Iraq, ordinary Iraqi Muslims chose to join the Americans against the Islamic extremists.

I explained our role in the intra-Islamic contest at Professor Nacos's blog. Excerpt:

With the lessons we learned at such high cost in post-war Iraq, surely we've laid the groundwork for a permanent peace operations capability - right?

Apparently not. Strategy thinker Thomas Barnett laments that we have yet to fill "the missing link for all the complex security situations out there where the traditional "big war" US force isn't appropriate." Barnett calls it a Department of Everything Else or, alternatively, a System Administrator or SysAdmin force.

I asked Barnett:

Opponents of Counterinsurgency and a permanent SysAdmin capability argue against the extraordinarily high price of the post-war in Iraq. They cite the reports finding that the "adhocracy" of the reconstruction led to billions of dollars lost to "waste, fraud and abuse".

I contend those reports are actually encouraging. Typically, technological and systems innovations incur inefficiencies, high costs, and extra waste in early development. The inefficiencies, costs, and waste are reduced as the technology or system is refined. The reports show areas where the cost of peace operations can immediately be reduced.

The inefficient "adhocracy" in the management of the Iraq reconstruction was in large part due to hostile politics within the US, unreasonable expectations of immediate returns on investment, and adverse conditions on the ground that sabotaged reconstruction efforts. If the domestic political frame can be fixed, a reasonable long-term planning approach applied, and initial security and stability mastered, then combined with general improvements, the cost of peace operations should be further driven down.

Of those 'ifs', the most important is establishing and maintaining security and stability from the outset of the post-war. As I said earlier, other nations were initially willing to invest in post-war Iraq but only on the condition security and stability were guaranteed. Obviously, sharing the cost would have helped. The downstream compounding costs and inefficiencies that were suffered in post-war Iraq all followed from our initial failure to maintain control of Iraq against the aggressive insurgency.

The cornerstone of my perspective on Operation Iraqi Freedom is that President Bush had, like President Clinton before him, only 3 choices on Iraq: maintain the toxic status quo indefinitely (default kicking the can), free a noncompliant Saddam (out of the question), or give Saddam a final chance to comply under credible threat of regime change (resolution).

* The Blix alternative, used by Clinton to retreat from his support for Bush and endorsement of OIF, was not realistic.

Whenever I debate OIF with anyone, I challenge that person to step into President Bush's shoes in the wake of 9/11 and defend their preferred alternative for resolving the Iraq problem. Most will refuse and, instead, double-down on criticizing Bush and OIF in hindsight. For those who have the integrity to try defending an alternative in context, it becomes apparent that Bush's decisions regarding Iraq were at least justified.

Some of the loudest opposition to OIF is from the IR realist school that believes Saddam should have been kept in power in order to check Iran. I think they're stuck in 1980, with the Shah only just replaced by the Ayatollah, and Baathist Iraq was thought to be the lesser of 2 evils.

Liberals understand that by the time of the Bush administration (either one works), the Iran-Iraq conflict was a cause of the region's problems, not a stabilizer. More importantly, given our thoroughly toxic relationship with Iraq by the end of the Clinton administration, our total distrust of Saddam, and his track record, I'd like to hear the IR realists explain in detail just how they would have negotiated a settlement with a noncompliant Saddam. They're effectively proposing Hitler should have been propped up in order to serve as a regional counter to the Soviet Union. Hitler + USSR = the worst of World War 2, not peace in our time. The IR realist belief that after 9/11 we should have trusted and empowered a noncompliant Saddam to deal with Iran on our behalf is madness.

The least thoughtful critics of the Iraq mission are the buffet-style critics. They accept the justifications for OIF and agree the world is better off without Saddam, yet say the US was wrong to stay for peace operations in post-Saddam Iraq. The critics who support the war while opposing the post-war in Iraq seem merely to be reacting to a palatable war versus a distasteful post-war. As I said to David Sanger, the US historically has followed victory in war with a long-term presence and comprehensive investment in the post-war. As the World War 2 victors, we learned the importance of securing the peace after the war and not repeating the post-war mistakes made by the World War 1 victors.

We gain little from war itself because war is destruction. The prize of war is the power to build the peace on our terms. The long-term gains we historically associate with wars have actually been realized from our peace-building following those wars. To defeat Saddam and then leave Iraq without first responsibly securing the peace would have been a contradiction of all our acquired wisdom as "leader of the free world", an inhumane abandonment of the Iraqi people, and an enormously risky gamble that invited new problems. As Paul Wolfowitz responded to critics of President Bush's post-war commitment to a liberal peace in Iraq, "We went to war in both places because we saw those regimes as a threat to the United States. Once they were overthrown, what else were we going to do? No one argues that we should have imposed a dictatorship in Afghanistan having liberated the country. Similarly, we weren't about to impose a dictatorship in Iraq having liberated the country."

Misinformation and mischaracterization have distorted the popular perception of the context, stakes, and achievements of Operation Iraqi Freedom with compounding harmful effects. They have obscured the ground-breaking peace operations of the US military in Iraq, thus obstructing the further development and application of peace operations. The distorted public perception has led to poor policy decisions by the Obama administration in the Arab Spring, most notably regarding Libya and Syria. Where President Bush positioned America after 9/11 to lead vigorously from the front as the liberal internationalist "leader of the free world", President Obama has reduced America to 'leading from behind' with predictable consequences. Bush gave Obama a hard-earned winning hand in Iraq, yet the Obama administration bungled the SOFA negotiation at a critical turning point. The premature exit from Iraq has cast doubt on the future of Iraq's development and caused the loss of a difference-making long-term strategic partnership.

The West Point cadet prayer expresses the aspiration to "Make us to choose the harder right instead of the easier wrong".

The outcome we desired was Iraq meeting its burden of proof and complying completely and unconditionally with the Gulf War ceasefire and UNSC resolutions. Saddam was given a last chance to comply - twice - and Saddam failed to seize the chance. Freeing a noncompliant Saddam from constraint was out of the question. Indefinitely maintaining and headlining the corrupted, provocative, harmful, and failing sanctions and 'containment' mission in Iraq was the easier wrong.

On March 19, 2003, President Bush ordered America into Iraq to do the harder right.

Also see:

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: Columbia students rally to support US troops Spring 2003;

10 year anniversary of the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom: final thoughts.

Eric

In November 2002, I weighed in on the looming Iraq confrontation in my opinion column for my school paper. My 1st post on this blog was dedicated to Army LT Ben Colgan. I said in my 3rd post that "the central battle of the War on Terror, in the present and for the future, is unequivocally being fought right now in Iraq." In fact, collecting my thoughts on the Iraq mission was the initial catalyst for starting this blog. 171 of my posts carry an "iraq" label ... 172 posts including this one. I've debated the Iraq mission with family, friends, classmates, and professors, on blogs, in on-line forums, and a television special with Iraqi and American college students.

The Democrats' current political advantage over the Republicans, including the presidency of Barack Obama, is built upon the demonization of President Bush over the Iraq mission, despite ample evidence that Bush and the Democrats were on the same page about Saddam. In fact, President Bush inherited the Iraq problem, together with the laws, policies, and precedents to resolve it, from President Clinton. As president, Obama upheld the justifications for military intervention in Iraq, though without endorsing OIF by name.

Given that many influential people are invested in an inimical, knowingly distorted narrative of the Iraq mission, explaining the Iraq mission seems like a quixotic exercise. Nonetheless, I do what I can.

The question that is being asked the most about the Iraq mission is the leading question, Was it worth it? Due to the popular misconceptions about the Iraq mission, however, I believe the most important question on this anniversary still is the contextual, Why Iraq?

Over the next few days, I'll look at my 171 posts with the "iraq" label and accrete my thoughts below. Make sure to check out the links.

Enjoy:

General David Petraeus: “If we are going to fight future wars, they’re going to be very similar to Iraq,” he says, adding that this was why “we have to get it right in Iraq”.

The objectives set forward by President Clinton to resolve our Iraq/Saddam problem were achieved with Operation Iraqi Freedom: Iraq in compliance, Iraq at peace with its neighbors and the international community, and Iraq internally reformed with regime change, albeit progress in the last goal has been less firm compared to the achievement of the first two goals.

To learn about the Counterinsurgency "Surge" in Iraq, I suggest this documentary video, the 2007 year-end letter from GEN Petraeus to his soldiers in Multi-National Forces-Iraq, these e-mails from Baghdad by Army Lieutenant Josh Arthur (a Columbia Class of 2004 graduate who served as an infantry platoon leader in the "Surge"), and the tactical innovations of Army Captain Travis Patriquin (R.I.P.).

President Kennedy explained the Iraq mission to West Point cadets ... in 1962.

Modern political Islamists are totalitarian, a Marxist revolutionary hybrid. Compare their efforts to Mao's Cultural Revolution. Many people seem not to comprehend that the terrorists are engaged in a clash of civilizations with us. In the clash of civilizations, terrorists welcome war. War is the terrorists' vehicle for unraveling the existing order. Terrorists, instead, cannot tolerate our peace. A trend-setting pluralistic liberal Iraq at peace is offensive and an existential threat to the terrorists.

In that light, I offer these essential questions about our commitment, clarity, and Why We Fight:

If American, and Western, progressivism has been conclusively discredited for its forceful displacement of native cultures like the American Indian tribes, then what is the ethical difference, after removing the Lebensraum aspect of autarkic Western expansion, between that and championing a liberal world order today in a 'clash of civilizations' against autocratic Middle Eastern regimes like Syria, Iran, Saddam's Iraq, or the Taliban in Afghanistan, and their fellow travelers like al Qaeda? Are we allowed to be progressive if we cannot, by self-imposed rule, classify our competitors as regressive? What's the practical effect if we restrict our engagement at the same time our competitors are totally committed to establishing an order that is incompatible with, and actively opposed to, our preferred liberal order?

I believe we need to restore our chauvinistic commitment to the American progressivism that shaped much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

I compared the merits of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom at Columbia political science professor Brigitte Nacos's blog in comments here and here. Excerpt:

Said more plainly, from the beginning, we could not win the War on Terror within the borders of Afghanistan, despite its obvious relevance to al Qaeda's campaign against the West. This is why Operation Iraqi Freedom was the right choice and the counter-insurgency "Surge" in Iraq so critical: from the beginning, an Iraq intervention, unlike an Afghanistan intervention, could provide the potential cornerstone for long-term victory in the War on Terror. Moreover, the basis for our Iraq intervention was already in place, developed under President Clinton.I also said this to Professor Nacos:

What's called neo-conservatism is just the progressive (interventionalist) liberalism of Wilson, FDR, and Truman, renamed. The bashing of neo-conservatism by self-described Western liberals, therefore, has led to the frustrating, self-defeating spectacle of influential people speaking liberal platitudes but quixotically opposing our definitively liberal strategy in the War on Terror. The effect of these liberals' tragic hypocrisy has been the degradation of the Western liberalizing influence on the illiberal regions of the world.

By the same token, an equally damaging effect of the attacks by self-described liberals on our liberal strategy has been the degradation within Western societies of the domestic understanding and support we need to adequately sustain the war/peace-building strategy endorsed by Presidents Bush and Obama. Therefore, a critical task of President Obama is to fix the deep damage done to his and Bush's foreign policy goals by Senator/Candidate Obama and other Bush critics.

From President Clinton's statement on the Iraq Liberation Act:

Let me be clear on what the U.S. objectives are: The United States wants Iraq to rejoin the family of nations as a freedom-loving and lawabiding member. This is in our interest and that of our allies within the region. The United States favors an Iraq that offers its people freedom at home. I categorically reject arguments that this is unattainable due to Iraq's history or its ethnic or sectarian makeup. Iraqis deserve and desire freedom like everyone else. The United States looks forward to a democratically supported regime that would permit us to enter into a dialogue leading to the reintegration of Iraq into normal international life.From President Clinton's announcement of Operation Desert Fox:

The hard fact is that so long as Saddam remains in power, he threatens the well-being of his people, the peace of his region, the security of the world. The best way to end that threat once and for all is with the new Iraqi government, a government ready to live in peace with its neighbors, a government that respects the rights of its people.

. . .

Heavy as they are, the costs of action must be weighed against the price of inaction. If Saddam defies the world and we fail to respond, we will face a far greater threat in the future. Saddam will strike again at his neighbors; he will make war on his own people. And mark my words, he will develop weapons of mass destruction. He will deploy them, and he will use them.

. . .

In the century we're leaving, America has often made the difference between chaos and community; fear and hope. Now, in a new century, we'll have a remarkable opportunity to shape a future more peaceful than the past -- but only if we stand strong against the enemies of peace.

In response to 9/11, the US could have pulled back from the Middle East, supported greater repression in the Middle East, or promoted greater freedom in the Middle East.

President Bush also could have reacted to 9/11 with a narrow focus on hunting down and killing terrorists, like President Obama's drone-centered campaign. (Bush used hunter-killer drone killings, too, but as one tool in the toolbox, not the centerpiece of his counter-terror strategy.) However, President Bush understood punishment and revenge did not amount to a big-picture, long-term solution.

Instead, the centerpiece of President Bush's big-picture, long-term response to 9/11 was revitalizing the American grand promise that animated the "free world" after World War 2. When he officially declared America's entry into the War on Terror on September 20, 2001, President Bush announced a liberal vision on a global scope and warned of a generational endeavor:

Americans should not expect one battle, but a lengthy campaign, unlike any other we have ever seen. . . . But the only way to defeat terrorism as a threat to our way of life is to stop it, eliminate it, and destroy it where it grows. . . . This is not, however, just America's fight. And what is at stake is not just America's freedom. This is the world's fight. This is civilization's fight. This is the fight of all who believe in progress and pluralism, tolerance and freedom. . . . As long as the United States of America is determined and strong, this will not be an age of terror; this will be an age of liberty, here and across the world.President Bush's liberal view of the American response to the 9/11 attacks aligned with President Clinton's liberal view of the American response to Saddam's noncompliance:

In the century we're leaving, America has often made the difference between chaos and community; fear and hope. Now, in a new century, we'll have a remarkable opportunity to shape a future more peaceful than the past -- but only if we stand strong against the enemies of peace. Tonight, the United States is doing just that.President Bush understood the obstacles and the ambitious scale of the aspiration. He recognized that a patiently assisted, controlled transition would be necessary for liberal reform to succeed in the Middle East:

For decades, free nations tolerated oppression in the Middle East for the sake of stability. In practice, this approach brought little stability, and much oppression. So I have changed this policy. In the short-term, we will work with every government in the Middle East dedicated to destroying the terrorist networks. In the longer-term, we will expect a higher standard of reform and democracy from our friends in the region. Democracy and reform will make those nations stronger and more stable, and make the world more secure by undermining terrorism at it source. Democratic institutions in the Middle East will not grow overnight; in America, they grew over generations. Yet the nations of the Middle East will find, as we have found, the only path to true progress is the path of freedom and justice and democracy.I observed in a January 2005 post:

Whether or not George W. Bush is doing a good job of the Presidency, I have to respect his decision in the War on Terror to make a try for it - [Francis Fukuyama's] the End of History. It is revolutionary and will either result in America's finest hour or the beginning of the end.President Bush positioned America to provide assistance for liberal reform, but he couldn't achieve his idealistic liberal vision alone. American liberals needed to become magnificent again and rally around Bush as he advanced the Freedom Agenda along with peace operations in Iraq to spark and empower a pluralistic liberal movement in the Middle East. Liberals over here needed to buy in to Bush's goals in order to convince liberals over there to buy in. They could not fairly be expected to trust the liberal intentions of the American president when American liberals refused to trust him, and worse, discredited and actively worked to undermine his agenda. Much of the anti-American propaganda in the Middle East was drawn from anti-Bush and anti-OIF misinformation legitimized by liberals in the West. Outside of Iraq, a few Middle East liberals recognized the lost opportunity of rejecting America's help, but most of them didn't trust Bush. Instead, when the liberals in the region attempted the "Arab Spring" revolution on their own, the result was predictable.

President Bush gave us the opportunity to reaffirm that we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our Fortunes, & our sacred Honor in order to battle the regressive challenge to our hegemony and make the world a better place. Instead, Bush's detractors used the opportunity to attack Bush with a false narrative in order to advance their own parochial partisan self-interests at the expense of the Iraq mission, our national interest, and a progressive world order.

Our peace operators - military, non-military, and contracted civilian - have been magnificent. But the rest of us shrank from President Bush's idealistic liberal vision. We the people let down our President, we let down our American heritage, and we let down the world. Rather than rise to the challenge of 9/11 with America's finest hour, we chose the beginning of the end.

Senator Joe Lieberman was an exception. He honored his liberal principles by his resolute support for the definitively liberal Iraq mission and the War on Terror.

Senator Joe Lieberman was an exception. He honored his liberal principles by his resolute support for the definitively liberal Iraq mission and the War on Terror. The antithesis of Senator Lieberman is President Clinton, the only American who appreciated the Iraq problem equally as well as President Bush. President Clinton initially supported President Bush and endorsed OIF based on Clinton's still-fresh presidential experience struggling with Saddam. However, where Lieberman stayed steadfast despite tremendous political pressure, even at the cost of his party, Clinton eventually caved to party pressure and turned on Bush and OIF.

One of President Bush's objectives for giving Saddam a final chance to comply in 2002-2003 was to bolster the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation. Bush faithfully followed the enforcement procedure on Iraq he inherited from President Clinton, although Bush deviated from Clinton's public case. However, although the UN sanctioned the post-war peace operations in Iraq, UN officials disclaimed the invasion of Iraq. By doing so, UN officials discredited the enforcement procedure that defined OIF, thus weakening the UN as a credible enforcer on WMD proliferation.